Audio that moves you: experiments with location-aware storytelling in the SFMOMA app

Stephanie Pau, SFMOMA, USA

Abstract

A pagan, a high-wire walker, and the stars of HBO’s "Silicon Valley" walk into a museum…Whaaaaat? The expanded SFMOMA features a transformed digital program with mobile technology at its forefront. Promoted as a not-to-miss part of the reopened museum, SFMOMA’s new mobile app is designed to be a head-up, phone-in-pocket experience that harnesses the power of location aware technology to deliver surprising, intimate, and human-centered art stories you can only experience in situ. Hear how SFMOMA partnered with a tech start-up, audio storytellers, and voices from beyond the museum world to upend tried-and-true conventions of museum audio. Radio and podcast talent, fiction writers, stand up comedians, sports figures, and magicians are among the creative collaborators tapped to develop surprising, just-in-time moments. The resulting experience combines the production values of Radiolab with the (seeming) awareness of "Her" to create a unique style of audio storytelling that moves you—through space, across time, and most importantly, on a human level. We’ll give a 360 degree view of the museum’s experimental approach to mobile storytelling—and how it’s landed (or not) with visitors. We’ll reveal the why and the how behind the app’s 20+ hours of new mobile content, and discuss ways in which the resulting stories present new (and hopefully more fun) possibilities for location-aware storytelling. We’ll also share findings from data collection and a recent mobile app evaluation. Along the way, we’ll address questions such as: How do you get institutional buy-in for decidedly unconventional ideas? What can museums learn from the radio and podcast renaissance? What do you gain—and what are the challenges of—creating linear, place-based audio journeys? Of the many content approaches experimented with in the app, which have resonated with visitors? And which have not?Keywords: SFMOMA, mobile app, storytelling, audio, sound, mobile, location-aware, evaluation

Introduction

The setting is the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, circa 2016. A mother and her son stroll quietly through a white-walled gallery space, pausing occasionally to view an artwork, read a label, or take a snapshot with their phones. Now and then they chat quietly amongst themselves. Suddenly they come to a halt. At the center of the room is a porcelain urinal, of the type one might find at a plumbing supply store. The urinal lays on its side, atop a pedestal, and its rim bears the signature “R. Mutt.” The pair’s bemused expressions reflect back at them in the object’s pristine white surface—and here, our scene takes a twist. Mother and son each take out a phone, tap the screen, and put their phones back into their pockets. Earbuds in place, they pause to listen to a audio track triggered by their arrival. A few moments later, mom looks at son, son looks at mom, and they burst out laughing in unison at the synced audio playing in their earbuds. Soon, they are examining the object from all sides, like archaeologists seeing an artifact anew. An impenetrable curiosity has been decoded and transformed into an iconic (and much more approachable) work of art: Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917/1964).

The scene above is based on a genuine visitor observation—one of dozens recorded as part of a multi-pronged evaluation of the SFMOMA app, an audio-first, location-aware mobile storytelling platform that was launched at the reopening of a dramatically transformed SFMOMA. The findings of this evaluation, particularly as they relate to the museum’s new storytelling approach, will be explored throughout this paper.

The Backdrop

On May 14, 2016, SFMOMA re-opened following a three-year closure and the completion of a 235,000-square foot addition designed by the architecture firm Snøhetta. The museum faced both opportunities and challenges in its new, scaled-up reality. To secure the long-term financial health of the expanded SFMOMA, the museum sought to increase its annual audience attendance goals by almost twofold in its re-opening year, and 30% in subsequent steady state years. How would the organization and its offerings meet the promise of a facility that now had more than twice the amount of gallery space and three times the public space of Mario Botta’s 1995 original? How could we introduce audiences to over a thousand new works from the Doris and Donald Fisher collection, while finding fresh ways to interpret works from the core collection?

With the support of a generous grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies, SFMOMA’s Content Strategy and Digital Experience (CSDE) division embarked on an equally transformative relaunch of its digital program. Visitors to the expanded SFMOMA can experience a suite of new on-site engagements that are designed to make them feel listened to and welcomed, that give them the tools to draw connections between art and their own lives, and “to break down the boundaries between art, entertaining and learning” (SFMOMA, 2010). The digital program includes a more accessible, visitor-friendly website and three gallery-adjacent interpretive spaces, which provide learning opportunities where and when they are most relevant and needed. Yet no tool is more equipped to support a model of “just-in-time” learning than mobile technology. Thus the pursuit of a new type of mobile experience—and a unique storytelling approach therein—became a keystone of the digital strategy.

It should be said that the decision to create a new mobile platform was never a foregone conclusion—it came only after we determined that the experience goals compelled it. After all, we had been down this road before. In 2010 the museum’s Interactive Educational Technologies team (now known as Interpretive Media) took on the in-house production of the museum’s first native mobile app, which supplanted a keypad-based audio tour with a touch-screen multimedia guide (Samis & Pau, 2009). It was the team’s most ambitious undertaking to date, involving four full-time staff to design and manage a new authoring environment, maintain a brand new fleet of museum-owned iPod touch devices and hardware, manage device check-out procedures, and create or creatively enhance hours of new and existing content—which was also being developed in-house (Samis and Pau, 2009; Gangsei & Svenonius, 2011). In short, we understood the significant expenditure of staff time, resources, and budget involved in the creation of a new museum-wide mobile experience. With a serviceable app already available, we were not interested in recapitulating a familiar experience model within shinier wrappings. We would only pursue a new SFMOMA app if we could offer something new.

The Stedelijk Museum is credited with inventing the first audio guide in 1952 (Tallon, 2009). The audio was delivered to visitors ears’ using radio technology—a single, looping broadcast heard over a wireless handheld receiver. In the ensuing six decades, the museum audio tour has become a ubiquitous, even expected element of the museum visit, and much energy has been put toward the continual improvement of its form factors. That early chrome receiver gave way to a Linnaean-like tree of evolving devices, each offering greater mobility and control over the delivery of audio (and eventually) multimedia messages. Keypads and wands allowed visitors to access standalone “stops” at random, thus freeing them from the constraints of a time-based linear tour. As cell phones became more ubiquitous, museums began to publish audio content through dial-in services. MP3 players offered even further convenience, and with higher fidelity sound, and today’s smartphones offer built in location-awareness, native accessibility options, and sumptuous touchscreen interfaces.

Despite these innovations in mobile delivery, far less attention has been paid to the messages themselves. Of course, it would be unfair to say that all audio tours live up to their reputations as boring, dry, and academic. Exceptional audio tours are certainly to be found at museums and cultural sites around the world. One stand out is Antenna Theater’s “Alcatraz Cell House Tour,” which was produced over two decades ago for the National Park Service and continues to serve roughly 3,500 guests daily. Narration by ex-cons, prison guards, as well as chilling sound effects—some recorded on-site—bring the history of the infamous, now-decommissioned prison to life (Antenna International, n.d.). Likewise, a rich tapestry of sound serves as the essential connective tissue for the Victoria and Albert Museum’s popular exhibition David Bowie Is… Broadcast to visitors through a network of regional transmitters, museum-provided wireless receivers, and over-ear headphones (Sennheiser, 2013), the audio featured a collage of interviews, multiple points of view, and music by the late rock idol. As with the Alcatraz tour, the David Bowie Is… audio experience is positioned as an essential element of one’s visit—enhancing interactions with both the environment and the objects on display.

Yet as a whole, in-gallery audio tours (in particular those produced by and for art museums) fail to push beyond the usual stories told about art, instead resorting to fact-based narratives that could just as easily be told through the “neutral” voice of a one-hundred-fifty-word text panel. In their emphasis on getting the facts right, many audio tours do not take full advantage of the medium’s greatest strengths. Sound designers may be given little latitude to explore new recording methods, editing styles, or even with integrating the basic building blocks of sound effects, music, and ambience. Historically, SFMOMA audio tours also tended towards conservative interpretations. This began to change in 2005, with the launching of the magazine-style podcast series SFMOMA Artcasts (Samis & Pau, 2006). In 2009, we turned our attention to in-gallery audio (Samis & Pau, 2009). In an effort to foster a more authentic and informal tone, we created nearly 100 new audio stops based around artist actualities and tape from a series of unscripted conversations between curators and educators. But experts and insiders remained the dominant voices, and those voices rarely expressed strong opinions, emotions, or personality. In regards to sound design, we continued to make sparing use of sound effects, music, and ambient sound, and only then in support of what was being expressed verbally.

As we embarked on the creation of the new SFMOMA app, we knew that in order to meet our lofty experience goals, we could not focus entirely on the platform and technology. It was imperative that we place as much energy towards telling great stories. To that end, we adopted a set of maxims that would guide our storytelling across platforms:

1. Share your passion with me generously, and with genuine excitement.

2. Offer me a voice of experience that I can only get here.

3. Give me something I can relate to from my lived experience.

4. Introduce me to artists as the complex, fascinating humans they are.

5. Surprise and delight me with unexpected perspectives and experiences. (Coerver, 2016)

The audience

Implicit in any storytelling approach is another time-tested mantra: know your audience. In 2013, in the lead up to SFMOMA’s expansion project, the museum and brand strategy firm Wolff Olins conducted a comprehensive market study to define key psychographic segments of Bay Area art-interested audiences that are most likely to engage with the museum. Understanding the motivations of the local community was strategic: San Francisco Bay Area residents were most likely to become members and repeat visitors, bringing friends and family along with them.

The study identified perceptual barriers visitors have in connecting with the art on view and suggested ways in which the museum could respond to these challenges and encourage repeat visitation. The study, which engaged 615 Bay Area residents, revealed that arts-interested individuals represent 60% of the population in the local region, but only 5% of them feel very knowledgeable about the arts and culture, and 28% do not feel knowledgeable at all. However, the overwhelming majority of all arts-interested people—upwards of 90%—report that they are eager to learn more (Wolff Ollins, 2013).

Importantly, respondents expressed that they desired not only information, but fresh and novel ways to engage with art. Several studies conducted at SFMOMA, including a recent focus group, have shown that artists’ working methods, motivations, and personal interests are the pieces of information that viewers desire most while standing in front of an artwork (Samis & Funk, 2014). Such findings are confirmed by studies of visitor needs and interests at other museums including The Museum of Modern Art (The Museum of Modern Art, 2012) and The Minneapolis Institute of the Art (The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1993).

But SFMOMA’s 2013 market study reveals another invaluable insight. While familiarity with modern and contemporary art is a key indicator of inclination to visit, even more important is the presence of two sentiments: that SFMOMA is “in line with my interests” and “a place for people like me.” Moreover, potential visitors indicated that the key attributes for a successful museum experience are “fun,” “warm,” and “inviting” (Wolff Ollins, 2013). This has been a challenge for all art museums, but particularly for those showing more challenging contemporary art.

Such findings suggested that SFMOMA needed to be more proactive in identifying new and more personally resonant ways for visitors to experience the art, and that it must find cultural ambassadors—both digital and in-person—to which visitors could relate and trust. Recognizing that potential visitors are interested in creative expressions across a variety of modes, SFMOMA sought to grow its audience by providing more points of access to modern and contemporary art beyond the discourse of academic art history. Back to the local angle, the museum also sought to place its art in a more deeply engaged dialogue with the rich tapestry of creative pursuits present in the San Francisco Bay Area.

No more Swiss Army Knives

The Wolf Ollins audience research in hand, we began the work of defining: (a) which of the audience segments we had the most potential to reach through the app, and (b) what set of features could best serve them. In February 2015, the app’s core project team—made up of staff from interpretive media, Web and digital platforms, graphic design, and information technology—enlisted Frankly, Green + Webb to facilitate a two-day user journey mapping workshop that would be key to defining our experience goals, target audience, and core feature set (Frankly, Green + Webb, 2015).

Participants included members of the app project governance committee—a mix of emerging and senior level staff from across the organization (exhibitions, curatorial, visitor experience, education and public practice, marketing and communications) whose expertise would prove crucial to designing a mobile service to support the successful deployment, messaging, and maintenance of the new app infrastructure and content. Governance committee members held the app team accountable for providing quarterly progress updates; they, in turn, committed to report back to their respective departments, to participate in the visioning process, and to assist in rapid prototyping and user testing.

Importantly, the core app team’s urge to try something new came with the invaluable backing of some members from the museum’s board. At SFMOMA, all public-facing digital projects are overseen by the Digital Experience Committee, an advisory committee of board members and experts from the tech industry. As leaders in tech, they argued strongly for pursuing a riskier approach than most museums would take, in the pursuit of something new.

The core app team, governance, and advisory committees all agreed on what we didn’t want to create: an app that tried to do everything for everyone, and none of it particularly well. This “Swiss Army Knife” approach, as we called it, became shorthand for the team’s “anti experience goal”—the litmus test against which all app-related proposals would be measured in the months ahead. Mapping the theoretical journeys, frictions, and needs of several persona, we determined that our target audience—those who represented the most “natural” audience for a content-based app and would gain the most from its use—were first-time visitors ages 13-45, with a focus on “Fact Finders” and “Self Improvers.” These audience segments were strongly motivated by the desire to learn, and from that learning derived more meaningful and personal connections with the art (Wolf Ollins, 2013; Frankly, Green + Webb, 2015).

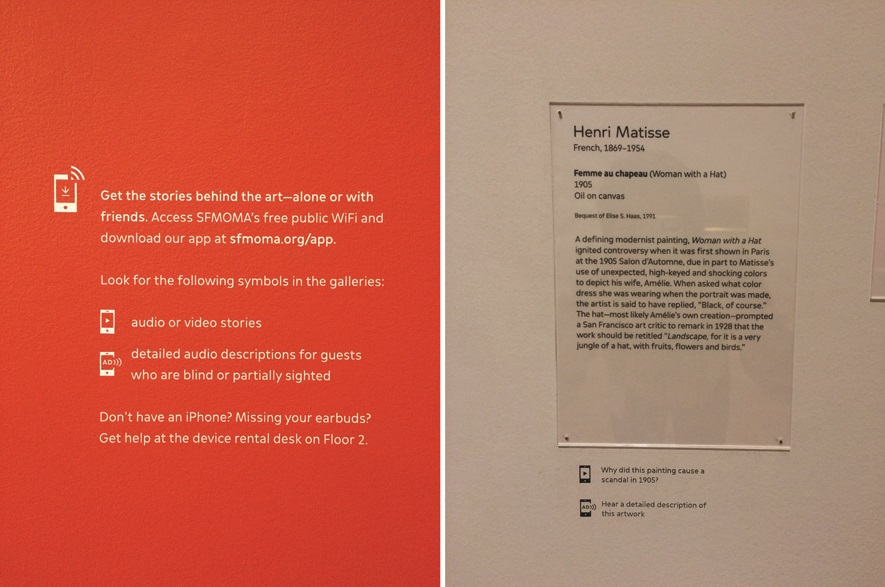

Finally, we came upon a decision that would shape the entire app experience, from content to platform to infrastructure. Unlike other museum apps, which could be used off-site as well as on, the SFMOMA app would be a destination program, an integral component of any visit; and, like the museum’s exhibitions and live programming, it could only be fully experienced on site. Content would be geofenced and available exclusively at the museum. To support the vision of a location-aware, story-first experience, the museum invested in comprehensive, free public WiFi, indoor surveys of all publicly accessible interior spaces, and a supporting suite of in-gallery signage.

Concierge services would be integrated into the app strategically, and only if they could facilitate a smooth transition from the outside-in. In-app ticketing moved users through the ticket scan lines more quickly; the digital membership card helped members do the same; current exhibition listings offered a way to prioritize one’s visit; and an auto-generated activity timeline would act as a post-visit souvenir of one’s visit. For everything else, including pre-visit planning and research, visitors could access the mobile-optimized SFMOMA.org. Additionally, dozens of new Visitor Experience staff were hired in the run-up to opening, and would be posted throughout the galleries to direct, orient, and answer questions from visitors in need.

Experiments in place-based storytelling at SFMOMA

We began the search for partners to help realize our vision. After considering RFP submissions from over a dozen producers and firms, SFMOMA hired Antenna International to be its primary audio production partner. Known today as one of the largest and most established producers of museum audio, it may be surprising to know that Antenna began as an experimental live performance group specializing in participatory theater augmented by sound. The aforementioned Alcatraz Cell House Tour was their first audio tour produced for a cultural site. We were eager to tap into the company’s experimental roots, as was Christine Murray, our primary producer at Antenna.

We partnered with a local start-up named Detour to develop the SFMOMA app technology, platform, and several long-form audio walks. Some members of the SFMOMA app team, myself included, had served as early beta testers for the new venture, and were floored by Detour’s combination of gorgeously-produced audio with accurate outdoor location-awareness. Rather than building the SFMOMA app from the ground up—an endeavor that was beyond the scope of our budget and in-house expertise—we realized that we had an opportunity to form a mutually beneficial partnership. The SFMOMA app would integrate key features of Detour’s backend, while Detour would gain a museum partner willing to manage the risks involved with developing what had until that point been elusive: a story-first, indoor, location-aware app experience. To ensure that the content received as much attention as the technology, Detour CEO Andrew Mason enlisted veteran radio journalist Marianne McCune as SFMOMA’s primary producer on a series of 15 to 45 minute Immersive Walk journeys.

Enlisting internal stakeholders was also key in developing a more welcoming, accessible, and experimental storytelling style. Over its two decade long history, SFMOMA’s Interpretive Media team had worked closely with its curatorial counterparts to plan exhibitions, interview dozens of artists, and to develop leading-edge educational media, digital tools, and physical learning spaces, each progressively more experimental. Over time, the museum’s leadership and curatorial staff had become habituated to the team’s ethos of risk-taking, as long as the results were supported by the visual evidence and current scholarship, and did not negatively impact the museum’s relationship to its artists.

Working simultaneously with Antenna, Detour, and a network of independent talent, the app content team created over twenty hours of new audio content by re-opening, with more added since that time. Listeners can choose from:

- Immersive Walks: 15 to 45 minute guided audio journeys on topics such as post-war German identity, the role of art in imagining the future, and why abstract art helps us to see the world differently. Though most walks take place inside of the museum, one goes outside to explore the history and architecture of SFMOMA’s surrounding neighborhood.

- Nearby Audio: Self-directed visitors can choose from hundreds of snack-sized 1 to 2 minute long audio responses to individual artworks. The voices of musical composers, comedians, artists, playwrights, aerial dancers, pagan ministers and many more are represented.

- Highlights: Staff-curated lists of Nearby Audio stories for must-see, on view artworks.

From a storytelling perspective, we had few museum-based models to work from. Our main sources of inspiration were Radiolab, This American Life, and other series produced by master storytellers in podcasting and radio. By listening, experimenting, and learning through trial-and-error, we can articulate the following set of internal guidelines for creating magical, immersive, and engaging location-based audio experiences.

Tell a story, not the story

Whether in long or short-form audio, we aim to keep audio stories brief and to the point. Nearby Audios are typically two minutes in length, preferably shorter. Within Immersive Walks, which offer the “carrot” of a continuous narrative or guiding personality, we may spend three to four minutes at most in front of a single artwork. There are multiple reasons for this brevity: visitors’ attention spans are short, the potential for “museum fatigue” is high, and an overabundance of information could foster a feeling of fragmentation and loss of interest.

Each app content production cycle began with a creative kick-off, which we dubbed “hooks” meetings because of their focus on isolating the one or two big ideas that might feel most relevant to a broad audience. The objective of these inquiry-based discussions was to channel visitors’ most pressing questions, to gather scholarly insights from the curators, and to collectively think of voices (preferably from beyond the museum) that might lend compelling, authentic, and relatable perspectives. The app team was then free to proceed with scripting and production in earnest, free from the permission-based culture that dictates any single, correct way to approach a work. As Gary Garrels, Senior Curator of Painting and Sculpture put it:

I am not a purist….I don’t think there is any one right interpretation about a work of art. So I gave my colleagues in “content” a lot of leeway….I have to say, they didn’t expect and didn’t ask to get involved in the curatorial decisions about what was in the gallery or how galleries were laid out. So I think there is a mutual respect of each others’ areas of expertise. (Rosenbaum, 2016)

Show some personality

The app offered us a platform for indulging our culturally omnivorous fantasies. We messaged high-wire walker Philippe Petit on Facebook to ask him to narrate an audio walk and amazingly, he said yes. We joined a Wiccan messaging board to scout for a pagan priestess with a keen eye for postwar American sculpture. We convinced Giants pitching coach Dave “Rags” Righetti to talk Dan Flavin with us. And we debated about Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain with comedians Martin Starr and Kumail Nanjiani of HBO’s Silicon Valley.

We also reached out to creatives whom we had long admired, including former McSweeney’s editor and fiction writer Eli Horowitz, with whom we developed our first fictional audio walk; documentary filmmaker Errol Morris; Avery Trufelman of the extraordinary design podcast 99% Invisible; and Third Coast International Audio Festival, with whom we co-commissioned a series of soundscapes that can only be heard in SFMOMA’s new public elevators.

Aside from making our own jobs more interesting, why go to the trouble? Audience research shows that many potential visitors were also likely to be culturally omnivorous—enjoying not only the visual arts but also film, music, performance, books and other forms of culture (Wolff Ollins, 2013). By extending our reach beyond the art world’s innermost circles, we could appeal to the visitor’s broader sets of interests and create a more relatable, accessible, and personally resonant museum experience.

Create magical intersections with physical reality

The audio tour genre has proliferated in part because it is understood as a visually non-invasive form of interpretation. With the ears as the conduit of information, the eyes are thus free to engage entirely with the art. Yet this simplistic view of audio denies the medium its full impact. Sound has the ability to transport the mind intellectually, spatially, temporally, and emotionally—all at once. As This American Life creator Ira Glass has said, “Radio is a very visual medium” (Abel, 2015). Location-aware technology introduces a set of new possibilities. In the SFMOMA app, we can use either radial or manually-drawn polygonal triggers to auto-start an audio piece as soon as the user steps into the pre-defined location. As a listener, this creates an uncanny sense that the narrator is “aware” and responsive to your presence.

To facilitate that fully immersive, near cinematic experience, our audio continually references surrounding physical environment. Rather than telling a visitor to simply “turn right,” consider a more site-aware description, such as “turn into the gallery just beyond that yellow wall on your right.” The effect of hearing accurate wayfinding descriptions can be both magical and reassuring to the listener. Be aware of the availability of nearby seating, and encourage visitors to take moments of rest. There is no way around it—in order to create a successful location-based audio walk, its creators must walk its path dozens of times to fully inhabit all of its features, and to get the timing just right. Find collaborators who are local to the site, or you risk creating a subpar experience.

At SFMOMA, we went as far as to purposefully install physical infrastructure that would support in-app stories. For example, in “Building for Art”—an Immersive Walk of nearly all seven floors of the expanded museum—we installed windows that allowed visitors to peer into a “seismic gap” that joins the 1995 and 2016 buildings, and ran an electric bulb to light its otherwise pitch-black interior. To create magical moments in “Neighborhood for Art”—an Immersive Walk about SFMOMA’s place in the South of Market neighborhood—we partnered with the California Historical Society to mount a physical exhibition of photographs by two artists featured in the tour. Moments after photographers Janet Delaney and Ira Nowinski are introduced, the app user approaches the entrance to the California Historical Society and are encouraged to go in. By flashing the SFMOMA app, visitors are given free entrance to view the exhibition as they complete that segment of the tour.

Make it fun, make it social

30% of SFMOMA visitors using the app have a strong learning motivation, but the desire to learn and make meaningful connections with the art takes place within the context of a leisure experience. When asked to state their motivations for using the app, 18% reported the desire to be entertained and have fun. Throughout the tours, we injected moments of irreverence, laughter, and delight. We tried not to take ourselves too seriously, and to reveal both the narrators and the artists as the complex and fascinating human beings that they are.

Finally, Just as with watching a movie, listening can be a social experience. SFMOMA app users may listen to the stories together through the app’s new syncing function—an antidote to the isolation of traditional museum audio guides.

What we’ve learned: insights from the mobile app evaluation

In fall of 2016, SFMOMA engaged Frankly, Green + Webb to conduct a study of the SFMOMA app experience. During the months of November and December 2016, field workers surveyed 488 visitors (270 users on both personal and museum-provided devices; 218 non-users who were both aware and unaware of the app) They conducted fifteen in-depth app user interviews, and recorded eight think-aloud usability sessions that were documented with Lookback software. Cross-tabulated against SFMOMA app analytics and the results of monthly visitor surveys, the study revealed key insights on these primary research questions:

1. In what ways is the SFMOMA app meeting its objectives?

2. Who is the audience for the app? What are the opportunities and barriers for increasing the reach of the app?

3. What is the impact of the app on the visitor experience? Does the app help visitors engage with the museum in meaningful ways?” (Frankly, Green + Webb, 2017)

Audience Reach

Historically, the primary audience for museum mobile guides have been tourists—both domestic and international—and skew toward a more mature demographic. We had no illusions that our target audience—first-time visitors aged 13 to 45, as many local residents as tourists—were highly aspirational. We were therefore delighted to discover that nearly half (47%) of SFMOMA app users are under the age of 35, and are actually more likely to be Bay Area locals (57%) than tourists (43%), especially international tourists (12%). Additionally, app users include not only first time (49%) but repeat visitors. Eleven percent of app users are “super” visitors who have been to the museum three or more times since it reopened. These numbers support the museum’s strategic objective of growing local audiences, and issues the museum a challenge: to continually refresh our content offerings in order to keep the app from feeling stale.

Though SFMOMA offers the same content through paid rental devices, visitors are encouraged to use the app on their personal devices. Signage installed throughout the museum and in the elevators promote the availability of the free downloadable app comprehensive free public WiFi. We offer free SFMOMA-branded earbuds at device checkout desks, and security officers and Visitor Experience staff have begun distributing them from their pockets. Finally, we offer charging stations (though admittedly not enough) in key rest points around the museum. The evaluation findings show that our efforts are making an impact. The majority of users (53%) have chosen to use the app on a personal device. “Shifting visitors away from museum-provided hardware to their own personal devices for mobile interpretation has been a goal of museums for the past decade….In this regard, SFMOMA’s app sets a new standard for a mobile museum service.” (Frankly, Green + Webb, 2017).

Yet we find that we could be doing more. Battery drains quickly on museum-provided devices, since units can’t go into power saving mode due to the protective casing. Pockets of weak WiFi are affecting the accuracy of location services in certain parts of the museum, and contribute to slow download times for visitors who are streaming content on personal devices. The unreliability of location accuracy in these zones can be particularly frustrating for Nearby Audio users. Having eliminated the punch-key number pad, these users lack a failsafe for calling up artwork if it doesn’t appear on-screen. These technical problems have clear impacts on user experience. 94% of users who didn’t experience any problems said that they were likely to recommend the app, compared to 81% of all users. Given that word of mouth is, quite remarkably, a key source of pre-visit awareness of the app (25%), addressing these technical bugs will be paramount in improving the reach and visitor satisfaction levels.

Duration

“It’s kept us in the museum longer. That’s for sure.” -Annie, survey taker

The duration of content ranges widely—from one-minute Nearby Audios to forty-five minute Immersive Walks that traverse multiple floors. In offering a range of options, we were taking a chance that, given a compelling story, app users would be willing to commit to lengthier, multi-floor experiences. App analytics demonstrate that on the whole, the completion rate of a scene (be it a Nearby Audio or an Immersive Walk)—has little to do with duration. In fact, the completion rate of a forty-five minute tour is on par with that of a one-minute Nearby Audio (SFMOMA, 2017). This is corroborated by user surveys, in which 75% of app users reported that the length of audio messages in the app was “just right” (Frankly, Green + Webb, 2017). On average, users are spending 116 minutes on the mobile app during their visit to SFMOMA.

Visitor responses to app stories

Visitors are noticing the difference in style and tone, and appear to appreciate the diversity of voices presented in the app:

“I like how we’re given not just curators or the artists talking about the art. There are other people…” -Chelsea

“I just had my first audio experience. Just amazing. I didn’t realize there was going to be stories, and music, and background…[I’m] delightfully surprised….they do it in a more storytelling way.” -Tammy

“The different voices. Different perspectives, and a good combination of entertaining yet factual.” -Eduardo

The app stories very purposefully reflect a wide range of not only voices, but a spectrum of approaches to scripting and sound design in both Nearby Audio and Immersive Walks. From story to story the intended effects are alternately earnest, emotional, circumspect, comedic, and at the far end of the limb, completely “out there.” Having no obvious models in the museum realm, we wanted to see what visitors’ appetites might be for the more experimental options. In-depth interviews with users revealed that for the most part, visitors are willing to play along. But the same piece of contact can land very differently with different visitors. And ultimately, the upper threshold for experimentation is determined by its relevance to the art.

Visitors responded positively to the comedy in “I Don’t Get It” because the jokes pertained directly to issues inherent in the artwork, or helped to resolve questions about the artist’s process or intent. By contrast, some listeners of the “Play by Play” Immersive Walk felt that the sports metaphors imposed themes back onto the artwork that weren’t necessarily native to the work itself. Compounding that was a multi-layered ESPN-inspired sound treatment, which some found cacophonous or grating.

“There was too much talking [on the ‘Play by Play’ walk]…It wasn’t relevant to the art, actually. They were trying to [relate]…Frank Stella with the race track. I mean, they killed the metaphor for me, honestly.” -Christina

Some fruit, it turns out, is too far out on the limb for app goers. Yet overall, the app is attracting a range of visitors who have different needs, motivations, and familiarity with modern art. In interviews, some visitors revealed a magical experience when the content appeared to answer their own questions.

“My mom’s like ‘that’s not art’ and we turn on the app and the first thing they say is ‘most people dismiss this type of art. It’s funny how they knew.” -Chantal and Eric

“I really love Rothko and I’ve never been able to articulate why. The description of the emotion that this particular narrator described was just spot-on what I’ve always felt but have never been able to articulate.” -Diane

Most users prefer to stick with the standalone Nearby Audios, but 34% of reported doing Immersive Walks. Those who did are, on the whole, delighted and surprised by their experience.

“When I went on the walk, I definitely noticed and learning things about the art…I was looking at work I wouldn’t have looked at otherwise. The walks presented me with things I wouldn’t have even asked about.” -Kari

“I liked when she was able to just tell me where to go and I would go there and I wouldn’t have to be like advancing to the next thing or whatever because it didn’t know where I was.” -Christina

Contrary to the perception of mobile apps and audio tours as isolating experiences, visitors reported that the app helped them to talk more with the people they came to the museum with, and gave them more confidence in looking at the art and in “doing” the museum visit:

“Lots of my friends don’t know about art. [I’d say to them] ‘Come in and laugh together.’ So many people don’t have any introduction to art don’t have to feel embarrassed to learn.” -Anonymous survey respondent

“We talked more.” -Chantal

Impact

Use of the app correlates to a more favorable perception of SFMOMA, and improved satisfaction with the visit overall. 75% of app users who did not experience technical problems reported being more or much more satisfied than they had expected, versus 70% for non-users. When asked what words they would use to describe the museum, those who used the app were more likely than non-users to choose the words “fun” (13% vs. 10%) and “participatory” (6% vs. 3%). Some visitors even cited the app as a reason to visit and to return.

“We might change to a member because of the app. We can’t get through in time, so we might upgrade to a membership. Tell them that. That’s a selling point right there.” -Annie

“I would go to a museum once every 5 or 10 years, but with this, I could have a different guided experience each time…I feel like it opens up an option that I didn’t feel like it was there before.” -Scott

“I actually thought it was a reason to come….If you’re not really into art, this actually gave you a window into it, a doorway….It could make you want to go. People who maybe didn’t even like museums, but said, ‘Let me give this a try because it will be a different experience.” -Leslie

What’s Next?

In many ways, the SFMOMA app has succeeded in its initial objectives. The content is resonating with much of our audience, and some users even see the stories as a reason to return. Furthermore, visitors who have had a positive experience with the app also have a better experience overall at the museum. Yet the true magic of a location-aware storytelling experience lies not only in the content, but in the content’s synergy with all aspects of the mobile service. Audio, location, and WiFi need to work together seamlessly—an operational challenge in a museum that rarely stays still. On the content side, the museum’s frequent artwork rotations require near-constant maintenance and in-house audio editing skills, since wayfinding directions and artwork mentions are baked into the audio. On the infrastructure side, changes in wall configurations (which happen often between shows at SFMOMA) require re-surveying indoor spaces to support location accuracy.

The appetite for risk-taking that got us here in the first place has served us well in the months following the launch of both a new app and new building. We are still learning, but we’ve also been proactive in making changes that will improve the overall mobile service. SFMOMA is investing in additional WiFi Access Points (WAPs). We’ve worked with colleagues across the organization to adjust exhibition planning, installation, and operational workflows, in order to improve a mobile service with many moving parts.

As far as next steps, new audio stories are already in the pipeline, location-aware technologies continue to evolve, and other museums are now looking to adopt the platform. No doubt, this collective energy will lead to not only a better mobile service, but new approaches to location-aware storytelling across the museum sector.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank her fellow core app team members, including Keir Winesmith and Sarah Bailey Hogarty (Web and Digital Platforms), and Bosco Hernandez (Design Studio). The development of a platform and infrastructure to support an indoor location-aware app—without the benefit of a building—was a herculean feat which could not have been accomplished without the tireless efforts of Keir, Sarah, SFMOMA’s IT and Operations teams, and our partners at Detour, in particular Andrew Mason, Ryan Holmes and Ulf Schwekendiek. De facto core app team members Chad Coerver and Erica Gangsei gave wise counsel to the project team at all stages. Thanks to Laura Mann and Lindsey Green of Frankly, Green + Webb, whose evaluation study provided us with many of the findings, recommendations, and photographs presented in this paper. In addition to Christine Murray (Antenna) and Marianne McCune (Detour), the author wishes to thank the many audio producers, scriptwriters, sound editors, artists, interviewees, and narrators who gave their time and talents to the project—alas, too many to name here. Finally, SFMOMA wishes to thank Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Institute of Museum and Library Sciences, whose generous grants supported the creation of the SFMOMA app project.

References

Abel, J. (2015). Out on the Wire: The Storytelling Secrets of the New Masters of Radio. New York: Broadway Books.

Antenna International. (n.d.) “Alcatraz: Project Info”. Exact publish date unknown. Consulted January 20, 2017. Available https://antennainternational.com/portfolio/alcatraz/

Coerver, C. (2016). “On Digital Content Strategy.” On SFMOMA.org. Exact publish date unknown. Consulted January 20, 2017. Available https://www.sfmoma.org/read/on-digital-content-strategy/

Frankly, Green + Webb. (2015). “SFMOMA Mobile App User Journey Mapping Final Recommendations Report.” Internal document. SFMOMA.

Frankly, Green + Webb. (2017). “SFMOMA Mobile App Evaluation: Findings Report.” Internal document. SFMOMA.

Gangsei, E., and T. Svenonius. (2010). “Mobile Means Multi-Platform: Producing Content for the Fast-Changing Mobile Space.” In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). Museums and the Web 2011: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2011. Consulted January 19, 2017. Available http://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2011/papers/mobile_means_multi_platform_producing_content

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts. (1993). “Interpretation at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.” Minneapolis, Minnesota. Consulted January 19, 2017. Available http://www.museum-ed.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/mia_interpretation_museum-ed.pdf

Morris Hargreaves McIntyre. (2016). “Culture Segments booklet 2016.” Consulted January 25, 2017. Available http://mhminsight.com/articles/culture-segments-1179

The Museum of Modern Art. (2012). “Questions Visitors Have about Works of Art in MoMA’s Galleries.” Internal document. Study conducted by The Department of Education at The Museum of Modern Art, May 2012.

Rosenbaum, L. (2016). “Robust App, Weak Tours: My WSJ Review of SFMOMA’s Technological Transformation.” Consulted January 27, 2017. Available http://www.artsjournal.com/culturegrrl/2016/07/robust-app-weak-tours-my-wsj-review-of-sfmomas-technological-transformation.html

Samis, P. and D. Funk. (2014). “Fisher Focus Group Analysis.” Internal document. SFMOMA.

Samis, P. & S. Pau. (2006). “‘Artcasting’ at SFMOMA: First-Year Lessons, Future Challenges for Museum Podcasters”. In J. Trant and D. Berman (eds). Museums and the Web 2006: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 1, 2009. Consulted January 22, 2017. Available http://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2006/papers/samis/samis.html

Samis, P. and S. Pau. (2009). “After the Heroism, Collaboration: Organizational Learning and the Mobile Space.” In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). Museums and the Web 2009: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2009. Consulted January 20, 2017. Available http://www.archimuse.com/mw2009/papers/samis/samis.html

Sennheiser Press Release (2013). “‘David Bowie Is’: Sennheiser Helps the V&A Bring Together Sound and Vision.” Published March 19, 2013. Consulted January 21, 2017. Available http://en-de.sennheiser.com/news-david-bowie-is-sennheiser-helps-the-va-bring-together-sound-and-vision-

SFMOMA Press Room (2016). “The New SFMOMA Announces Transformed Digital Strategy.” On SFMOMA.org. Published May 2, 2016. Consulted January 20, 2017. Available https://www.sfmoma.org/press/release/new-sfmoma-announces-transformed-digital-strategy/

Tallon, L. (2009), “About that 1952 Stedelijk Museum audio guide, and a certain Willem Sandburg.” Musematic. Published May 19, 2009. Consulted January 19, 2017. Available http://musematic.net/2009/05/19/about-that-1952-sedelijk-museum-audio-guide-and-a-certain-willem-sandburg/

Wolf Ollins. (2013). “Comprehensive Market Study for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.” Internal document. SFMOMA.

Cite as:

Pau, Stephanie. "Audio that moves you: experiments with location-aware storytelling in the SFMOMA app." MW17: MW 2017. Published January 31, 2017. Consulted .

https://mw17.mwconf.org/paper/audio-that-moves-you-experiments-with-location-aware-storytelling-in-the-sfmoma-app/